As England enters a third lockdown where all people are ordered to “stay at home,” at Spectacle we are reminded of a community in Clapham Old Town, Lambeth SW4 that was told to “get out” of their homes.

In Rectory Gardens, there lived a group of creative and industrious people. As young artists and divergent thinkers they turned a derelict bombed out row of uninhabitable houses into a flourishing artistic community. For forty years they lived in a housing backwater largely unaffected by social housing policies, despite sporadic attempts by the council to “formalise” the street. They created a housing cooperative, until Lambeth, the ‘cooperative Council’ began taking their “million pound” houses from under their feet. The community that now included the vulnerable, elderly, and unwell, was broken up and dispersed.

A Tragedy in the Commons

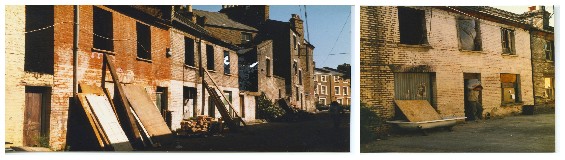

Rectory Gardens (RG) is a L shaped Victorian pedestrian street in Clapham Old Town SW4 that was badly damaged by bombing during WW2. In the late 1960s and 1970s, the decimated houses attracted a group of squatters who saw the opportunity to create a utopia. This motley crew of characters with their own ideologies, housing needs, and reasons for living outside of the norm, formed a collective community which lived in relative harmony for four decades.

By the 1980s these squatters had revitalized the houses, and formed a housing cooperative. Rectory Gardens offered a home for all kinds of artists, free-thinkers, draft dodgers, and other socially liminal characters. Through the 80 and 90s, it remained a diverse community at the epicentre of a flourishing arts scene.

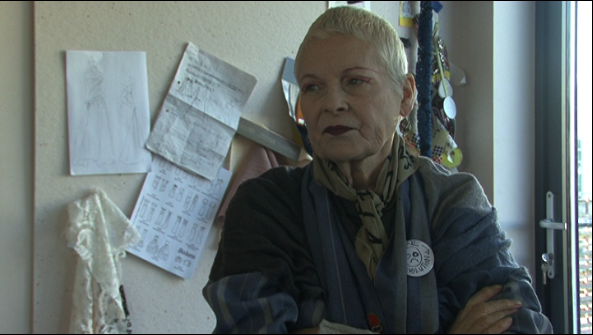

The street was host to an industrious community of artists, musicians, poets and unconventional ‘free thinkers’ who found a cheap way of living while developing their creative endeavors. It became a hub of cultural activities initiating art studios and cafes that brought life to the area. Spectacle interviewed both Vivienne Westwood and Maggi Hambling about the value of Rectory Gardens’s cultural contributions.

Residents of this dynamic community were the initiators of much that made the area distinct and attractive, the skate park and cafe on clapham common, Cafe des Artistes, Fungus Mungus, Voltaire Studios, bric-a-brac shops, rehearsal studios, artisan crafts and pool of skilled creative labour. The street itself had a public garden that served as a safe play area in the day and a performance and social space in the evening.

As with any tragedy, their success was key to their end as well. The artistic growth contributed to the popularity of the neighborhood and ultimately its subsequent gentrification. The council had its eyes on the properties, and though the residents tried to work with the council to legalize their living arrangement the deal fell through. The residents were recently evicted by Lambeth Council, who sold the houses to a developer on the private market.

Evicting the community was devistating for the mental health and well-being of many of these elderly and vulnerable residents. They lost not only their homes but their community and support networks. Many struggled to live away from their home of forty years, some died or were sectioned. Housing is integral to well-being, a point overlooked by this profit driven housing department.

Spectacle at Rectory Gardens

In the spring of 2014 Spectacle was contacted by the residents of Rectory Gardens. They wanted to record the final months of their squat-turned housing-cooperative. Rectory Gardens had been a lively arts community for over forty years, but growing conflict with the local council left the residents desperately fighting to avoid eviction, something that perhaps some media advocacy and intervention could assist them with, they believed.

During our preliminary engagement with Rectory Gardens, Spectacle offered training to any residents who were interested in filming techniques. Spectacle conducted workshops where participants learned camera techniques, collected peers’ stories, and collectively discussed the footage and ways to continue the production process. The production process was dictated by the participants themselves, and they shaped the narrative scope by inviting ex-residents to contribute with their memories. This work developed into an archive of oral histories of the street.

The production has continued for over six years, far longer than the initial few months originally envisioned. Together, Spectacle and Rectory Gardens residents have collected over 150 hours of footage including: long interviews with residents; key events on the street; residents resisting evictions; historic footage filmed by residents during the 90s; and residents in their new flats, reflecting on living away from their community where they lived for decades.

During Spectacle’s engagement, RG has been dismantled through evictions and relocations, and the residents have been scattered to various and disparate areas of the borough. The street, on the other hand, has been transformed to make way for the arrival of new wealthy tenants.

Framing the Street

Spectacle’s video archive of Rectory Gardens brings out many topical themes and offers inspiration for the post-Covid City through an examination of the past. Rectory Gardens is a portrait of forty years of resistance to the government housing policies.

The houses themselves were initially built as philanthropic poor-quality Victorian housing for low-income workers. After

Rectory Gardens was bombed and left derelict post WW2, it provided a solution for postwar homelessness through squatting. It offered fertile ground for experimenting with alternative ways of living, resisted the “slum clearance” in the 1970s, Thatcherism, and the sale of social housing in the ‘80s. Their methods and ideologies represent a range of approaches including anarcho individualism, anarcho-syndicalism, socialism, capitalism of small artisanal businesses looking for cheap space, and the daily necessity of the socially excluded and the legally marginalised.

By the 2000s, the constant push to turn London’s affordable housing into profit, was nibbling at the edges of Rectory Gardens as well. The insidious forces of “regeneration” and contemporary privatised gentrification have been endemic in London where, even by global standards, the commodification of real estate is extreme. Through eviction and rehousing the community was broken up, and the squatters were replaced with live-in guardians, the modern sanitised, privatised version of squatting.

It’s important to note that not all parts of London have been equally gentrified, and Lambeth Council, where Rectory Gardens is located, was famous for its tolerance of alternative housing organisations and leftist leanings. They referred to themselves as ‘the cooperative council’ and ‘Red Ted’ Knight and his ‘Socialist Republic of Lambeth’ were the bete-noir anti hero of the tabloids. There were many houses like Rectory Gardens which were uninhabitable after the war, and Lambeth had few resources to deal with them. Squatters quickly took advantage of the council’s disinterest and moved into these spaces. Lambeth greatly benefited from the labour of these groups, and many cooperatives were able to legalise their situation, but RG was not.

The Project Now

The filming part of this project has come to a close, and we are looking for partners in the next phase – telling the story of what has disappeared.

We are searching for funding and partners to assist in bringing the dispersed community together again for an online participatory editing process. The process will let the former residents of Rectory Gardens tell their story, by sifting through the 150 hours of footage and drawing out narratives and themes to share with a wider audience.

Searching for Partners for Rectory Gardens Online Participatory Video Project

If you are interested in exploring collaborations or can suggest potential funding streams please get in contact. We welcome academic researchers, activists, social historians, and all others.

Read more about our model and past projects.

Please get in touch with projects@spectacle.co.uk or subscribe for more information.

For updates check our other blogs.

This project is relevant to: well-being, health, housing, social housing, urbanism, urban planning, human geography, sociology, participatory methods, co-creatation, co-authorship, knowlege sharing, community filmmaking, and participatory film.

Spectacle Homepage

Like Spectacle Documentaries on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram, Vimeo, Youtube and Linkedin