By Mark Saunders, 12 September 2007

Originally published by Mute Magazine

Whatever the overruns on time and cost, one thing the London 2012 Olympics is certain to deliver is a huge public debt. The enormous bill for two weeks of telematic sport is legitimated by promises of urban regeneration but in reality the games are a corporate landgrab facilitating the looting of nature and labour as prices go up and people are pushed out, argues Mark Saunders

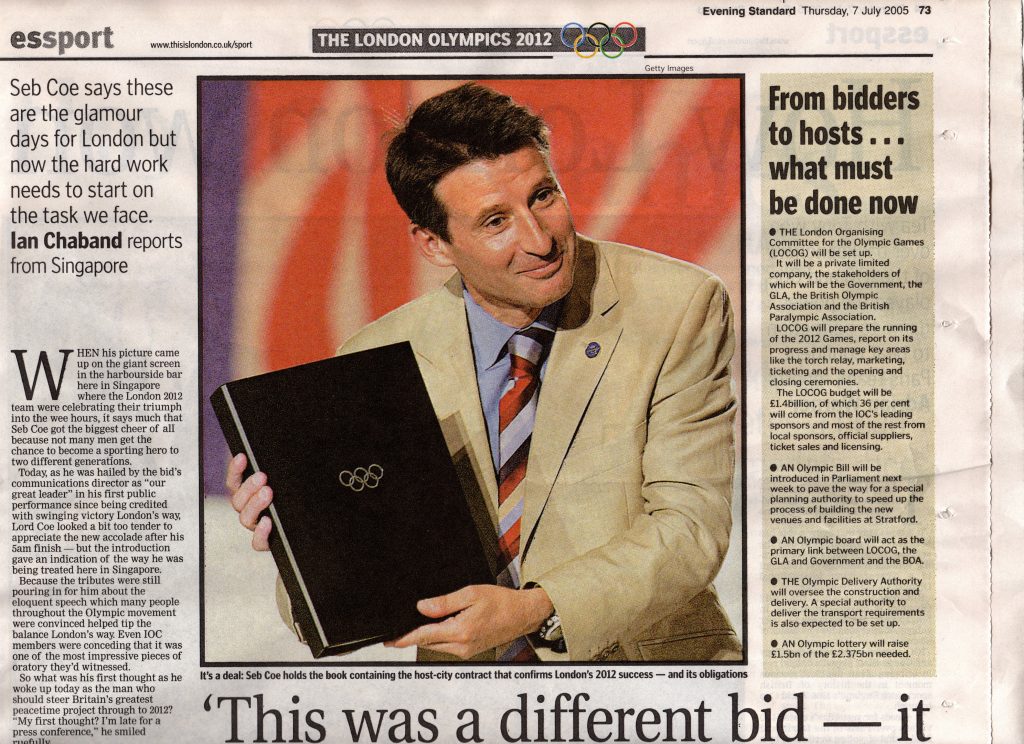

News item, 2005 commenting on London Olympics, 2012

On the 6 July 2005, crowds of Londoners gathered on Trafalgar Square for an Olympic ‘decision day’ event. With no real expectation of winning, the Olympic Bid Team had billed it as a ‘Thank You London, Thank You UK’ day. Crowds could watch on giant screens the International Olympic Committee’s decision on the host city for 2012. It would probably be Paris.

Up on the platform, a host of London 2012 ambassadors expectantly held hands. All white teeth, perma-smiles, and synthetic fabrics, they prepared themselves for sporting and gracious defeat. It would surely be Paris.

At 12:49, the International Olympic Committee president, Jacques Rogge, made his dramatic announcement. The winner is… pause… pause squared… (the open mics amplifying the deafening silence)… London.

News item, 2005, commenting on London Olympics, 2012

A moment of disbelief… Not Paris? Then the crowd erupted in celebration.

That evening, TV newsreaders had particularly puckered brows and quizzical looks as they announced the news. Despite being the top story, it had the ‘would you believe it’ feel of the light-hearted ‘and finally…’ item, intended to put viewers back into a happy consumer mindset for the rest of the night’s fare.

NO DAY AFTER

The euphoria was destroyed within 24 hours when the 7/7 bombs exploded on London’s public transport. Four suicide bombers killed 52 commuters and injured 700. The events of the day before seemed remote, doubly unbelievable and distant. Some frivolous aberration from a naïve time the other side of a watershed moment.

Seb Coe and his Olympic Bid entourage returned to London to a muted welcome, after celebrating all night at what Coe described as the ‘mother of all parties’ on the banks of the Singapore River. Despite being ‘shocked and saddened’, their return had the air of galavanting playboys who had had a high old time while at home all hell let loose.

The bombings overshadowed all debate. In the public consciousness, the Olympic party in Trafalgar Square had had no ‘day after’. As the media dust settled, the London Olympic reality slipped back into view. Like some post-traumatic flashback, computer animations of the Olympic site on TV showed a grey expanse turning green. Dome-shaped structures mushroomed everywhere like 1950s lunar bases linked by wobbly bridge walkways.

Out went the sporty types, in came the suit-and-tie squad. It was the men’s tri-athletes: legal, PR, and planning. It’s time to hide behind the sofa, because this is the invasion of the technocrats all those politicos were warning you about.

WHY LONDON?

News item, 2005, commenting on London Olympics, 2012

The main reason London won was because it was not France. The Olympics is basically corporate America in Lycra. The US Olympic Committee receives 20 percent of marketing revenues and 12.75 percent of TV income from the Olympic Games – a dominance that concerns other National Olympic Committees. The US is a serial Olympic host: St. Louis in 1904, Los Angeles in 1932 and 1984 (and a bid for 2016), Atlanta in 1996, and Winter Olympics at Lake Placid in 1932 and 1980, Squaw Valley 1960 and Salt Lake City in 2002.

Since the Gulf War, the US has been virulently anti-French. There was no way that McDonald’s or Coca Cola, the latter a major sponsor for the past 80 years, were going to let those smug surrender monkeys enjoy the reflected glory and glitz of corporate America. After all, it was France that forced McDonalds to deviate from the one-size-fits-all burger because of their finicky eating habits.

The Bush regime and its business allies know all about mega-spectacles like the Olympics. Recall 1 May 2003, when Bush landed a fighter jet aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln, delivering his Iraq victory speech standing in front of a giant ‘Mission Accomplished’ sign.

It’s all about image. And such sophisticated connoisseurs of the spectacle are hardly likely to squander the global arse-kicking razzmatazz of their athletes sweeping up medals just to puff up the French cock… er…

A MODEL OF MULTICULTURALISM

Rather than confessing to it being a reward for British military support of the US in Iraq, and perhaps to pre-empt accusations of bribery, the London Olympic Committee claimed the UK was favoured over France (which, after all, had all the infrastructure in place) because of London’s (and particularly East London’s) tolerance, multiculturalism, and ethnic diversity. There is nothing in the constitution or history of the International Olympic Committee that betrays this concern.

News item, 2005 commenting on London Olympic bid, 2012

In 2006, an international coalition of human rights organisations issued a joint statement saying that the International Olympic Committee has failed to protect Olympic ideals citing continuing human rights violations and political propaganda abuse of the Games by the Chinese government.

Multiculturalism? It would be surprising if the IOC even thought about it. Had it done so, it would soon have had concerns about the UK. In one typical week earlier this year, stories in the national newspapers included the following:

The Conservative homeland security spokesman, Patrick Mercer, stepped down after saying that being called a ‘black bastard’ was part-and-parcel of life in the armed forces.[1]

Magistrate reprimanded for ‘bloody foreigners’ outburst in court. Mr Mitchell, a magistrate for 36 years, did not accept the punishment issued by the Office of Judicial Complaints, part of the Department for Constitutional Affairs, and remains on the active list.[2]

Police accused of brutality after officer beat 19 year old woman during arrest at night club. An investigation into alleged police brutality was launched last night after a black teenage epileptic woman was filmed being repeatedly punched by a policeman, while two colleagues held her down outside a Sheffield nightclub.[3]

These are all examples of institutional racism. It may be that on the East London street and within communities, there is a certain class based solidarity and community cohesion across and beyond race. But to describe the East End as a model for multiculturalism is simplistic. While the area does have a long history of fighting fascism and racism, from resisting Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in the Battle of Cable Street in 1936 to Bengali youth reclaiming Brick Lane from the National Front in the 1980s, it sadly has often been in response to an equally long history of racism and intolerance.

In 1968, ex-Tory minister Enoch Powell’s speech in which he predicted ‘rivers of blood’ if black immigration continued inspired several hundred London dock workers to strike and stage an ‘Enoch is right’ march.

In 1986 Tower Hamlets Liberals proposed to put hundreds of homeless families (mainly Bengalis) into ships moored on the Thames. A report by the Commission for Racial Equality in 1988 found Tower Hamlets Liberal Council guilty of allocating ethnic minorities disproportionately to poor quality estates.

In local elections in 1995, the total number of votes cast for far-Right parties in Britain amounted to just over 20 thousand. The vast majority were cast in East London. On 5 May 2006, the British National Party (BNP) gained 11 of the 13 seats it contested in the East London districts of Barking and Dagenham, becoming the second biggest party.

There are incidents of race hate crimes in the Olympic area, but there is also the manipulation of racial tension for political ends. In her paper, ‘Playing the ethnic card – politics and ghettoisation in London’s East End’, Sarah Glynn details how local politics has linked territory and race.[4] From the mid-1980s, the Tower Hamlets Liberals had in effect used housing policies based on ethnicity to divide and rule. They had systematically shifted the blame for housing shortage onto the homeless (predominantly Bengalis) while continuing to sell off housing and land.

High unemployment, scarce and neglected housing, excluded from the dockland development boom – there were reasons for local residents of the Isle of Dogs to be angry. The Island’s relatively small Bengali population provided an easy scapegoat. Similarly, the Olympics is bound to intensify competition for housing, especially with an expanding buy-to-let sector hyping rents. Locals, already squeezed between two of Europe’s biggest business districts, Docklands and the City of London, are going to find themselves surrounded on all sides by intensive gentrification. It would be ironic if racial tension were to deflect from class-based ‘yuppies out’ hostility to the gentrification and privatisation of space in the East End that the ‘multicultural’ London Olympics will presage.

INFRASTRUCTURE

Paris was favourite to win the Games because it has much of the necessary infrastructure in place. In opting for London, the International Olympic Committee must surely have chosen to ignore the UK’s unique history of infrastructure and stadia construction fiascos. The newly refurbished Wembley Stadium was originally set to cost under £400 million. The official overall cost of £757 million did not include the overruns and compensation compromises on the building works of £352 million. It opened two years late. The Millennium Dome, originally estimated to cost the National Lottery £399 million, came in at least twice over budget and only just made the New Year’s Eve opening for which it was built.

During a debate on the economic and social benefits of the Olympics in the upper house, Lord James, a Tory peer, said that big business, including McDonald’s, BT, and British Airways, had run rings round the Government when negotiating sponsorship deals for the Dome. The Dome organisers had negotiated flawed contracts with major sponsors and had ended up receiving a fraction of the money they expected.

The overrun on the Dome all occurred on the management costs and the running of the Dome and its ancillary services […]. It resulted eventually in what amounts to an £811 million learning curve for the Government, which I sincerely hope they will be marking and using extensively in the lessons for the Olympics.

London Tonight, itv local,

So the IOC must have thought it was worth a shot, statistically, that this time it would all go smoothly. But then they have nothing to lose.

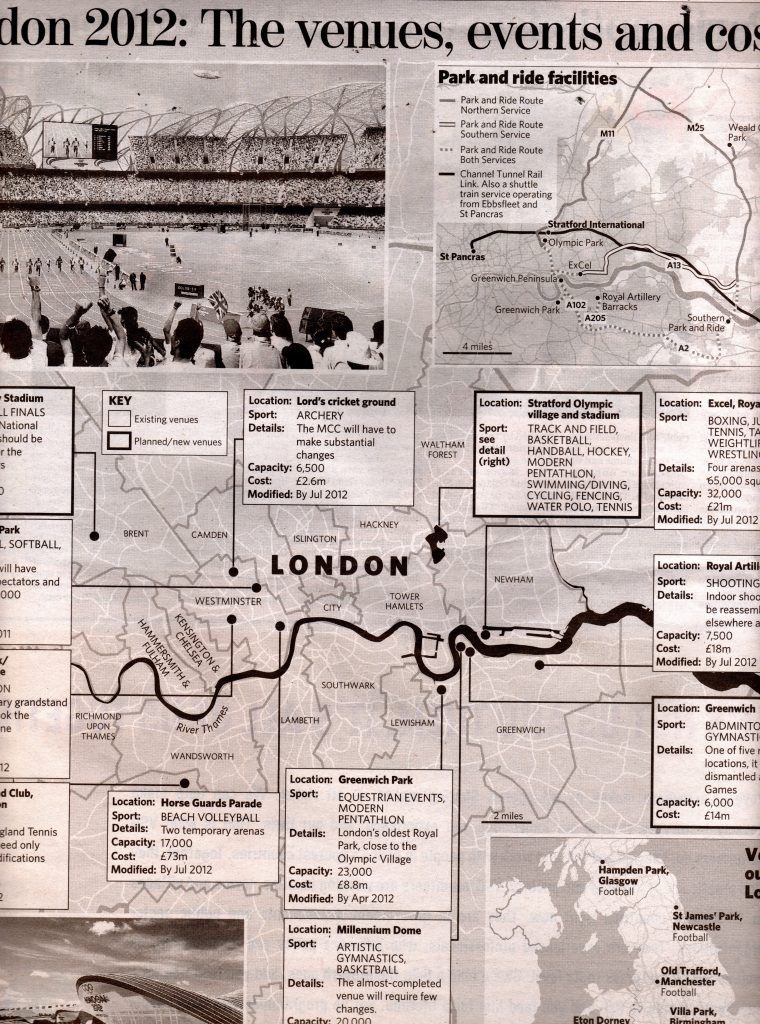

ONE FOR THE MONEY, TWO FOR THE SHOW

As with the Poll Tax the media response to the Olympics has tended to concentrate on the costs and its implications for taxpayers, rather than the social injustices. The total Olympic budget is £9.3 billion, an increase of £5.9 billion from the original budget of £3.4 billion. When Tessa Jowell, the then culture secretary (now Minister for the Olympics), admitted in the House of Commons that the initial budget had not included the 17.5 percent cost of VAT on the construction of the venues and infrastructure, there were cries of incompetence. Nowhere was it remarked upon that nearly every bid is undervalued, not through incompetence but as a strategy. For London taxpayers, the Olympics are indeed a big story. Financing is split between the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) and the London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (LOCOG). The ODA will ‘build the theatre’ – the infrastructure, venues, land remediation, and so on – and will be funded jointly by the public sector (64 percent), London taxpayers (13 percent), and the lottery (23 percent). The LOCOG, meanwhile, will ‘put on the show’ – everything from the opening ceremony to the closing ceremony. This expenditure will be funded by the private sector out of ticket and merchandising sales, TV rights, and sponsorship. All the real costs and risk are therefore taken on by the public sector.

Sydney 2000 ended up costing over twice the pre-bid figures, according to the auditor-general of New South Wales. In Athens, total costs will be at least four times as high as the bid committee’s initial budget. The IOC insists that host nations cover any cost overruns. Basically, the public would never accept the Olympics if it knew the real cost.

THE PROMISES

The media were equally uncritical of the promised regeneration of East London, regurgitating the public relations press releases without seeming to question the ‘empty land’ myth or whether regeneration through sporting facilities is genuinely worthwhile.

News item, 2004, commenting on London Olympics, 2012

A common feature of regeneration schemes is verbal promises given by people who are clearly unable to deliver those promises. Lord Coe, director of the London Olympics, promised a successful bid would bring: ‘9,000 new homes, many affordable for local people’ and new shops, offices, community and health facilities, plus world class sporting facilites in a new park. Local businesses are likely to benefit from the influx of new visitors and from potentially winning contracts to service the Games.[5]

Affordable housing sounds good, but a recent, high profile scheme for subsidised ‘low-cost’ rent-and-buy housing in the East End requires applicants to have an annual income of at least £28,758 (£32, 644 for couples).[6]

The Olympics are very likely to have the opposite effect and make housing unaffordable for local people. In the run-up to the Sydney Olympics 2000, rent escalated and intensified evictions in the neighbourhoods alongside the Olympic development. In Barcelona, the 1992 Games were partly responsible for massive increases in costs of living in the city: between 1986 and 1992 the market price of housing grew by an average of 260 percent.

While the number of affordable new homes promised tends to come down over time, so the projected jobs figure seems to go onwards and upwards. A 2002 survey by engineering consultants Ove Arup calculated that

The Olympics will lead to the creation of 3,000 jobs and 4,000 new affordable homes for people in East London.

By 2007, London’s Employment and Skills Taskforce and the London Development Agency (LDA) were talking of the Olympics creating up to 50,000 new jobs in the Lower Lea Valley.

Dee Doocey, chair of the Committee for Economic Development, Culture, Sport, and Tourism, the leading committee on the London Assembly for scrutinising the Olympics, said locals could miss out unless language and construction skills were ‘urgently’ improved in the East London boroughs. As she said on her own website:

The last thing we need is another Docklands, where many of the newly created jobs did not benefit local people.

Responding, the LDA pledged to make it a ‘priority’ to ensure locals in the five Olympic Boroughs of Greenwich, Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets, and Waltham Forest benefit from the new opportunities. Of the 720,000 people of working age living there, a quarter have no qualifications and, of these, over 60 percent are unemployed. Commenting on the announcement of a new ‘Living Wage’ for London of £7.20 an hour, Doocey, said:

The Mayor and Seb Coe signed an ‘Ethical contract’ with London Citizens before winning the Olympics, promising a Living Wage for everyone involved. Yet to date, no Living Wage has been included in the contracts allocated and Seb Coe told the London Assembly that ‘any of the issues about a living wage is a consideration, not a condition’. This is of great concern because LOCOG will be letting contracts for all the traditionally low paid jobs such as catering and cleaning.

As for local businesses exploiting the games, as Coe had suggested, it is more likely that existing businesses will be endangered. The director of H. Forman & Son, the UK’s oldest established salmon curer and one of the Lea Valley’s biggest and oldest companies, recently took to bringing a large aerial photograph of the proposed Olympic site to meetings, in order to show that far from being empty the Marshgate Lane area of Stratford includes 350 businesses with 15,000 employees. According to plans, these premises would be bulldozed to make way for the games.

The Institute for Practitioners in Advertising describe the marketing prohibitions defined in the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Bill, which sets up the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) as ‘so extreme that it could technically lead to pubs being prosecuted for using chalkboards to flag up [TV] coverage of the Games’.[7] Protected Olympic trademarks include use of the words ‘Olympic’, ‘Olympiad’, and ‘Olympian’, ‘2012’, ‘London 2012’, ‘games’, ‘medals’, ‘gold’, ‘silver’, ‘bronze’, ‘sponsor’, ‘summer’; insignia such as the 2012 Games logo (and mascots), the Olympic rings, Team GB, the British Olympic Association and the British Paralympic Association logos, London’s bid logo; derivatives of London2012.com; and the Olympic motto ‘Citius, Altius, Fortius’ (Faster, Higher, Stronger).[8] Ludicrously, 31 small firms throughout London reflecting the Greek diaspora will be forced to change their company names and shop fronts as a result of trademark conditions.

The companies likely to benefit are Coca Cola, McDonalds, and Visa, which have bought exclusive worldwide marketing rights via the Olympic Partner Programme. The BBC states that the IOC have made £790 million marketing revenue over the last four years from corporate sponsorship (35 percent of total), while LOCOG estimates that £580 million, or 40 percent of its operating budget, will come from this source.

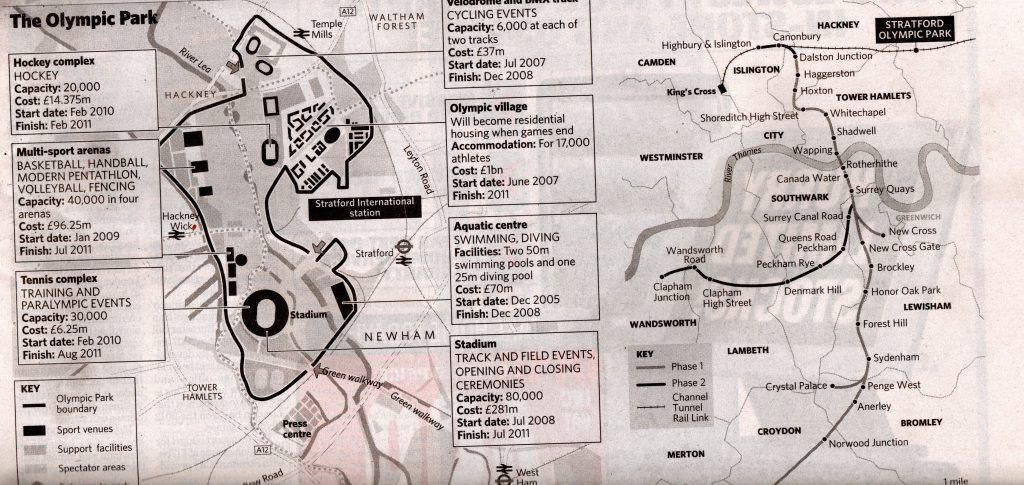

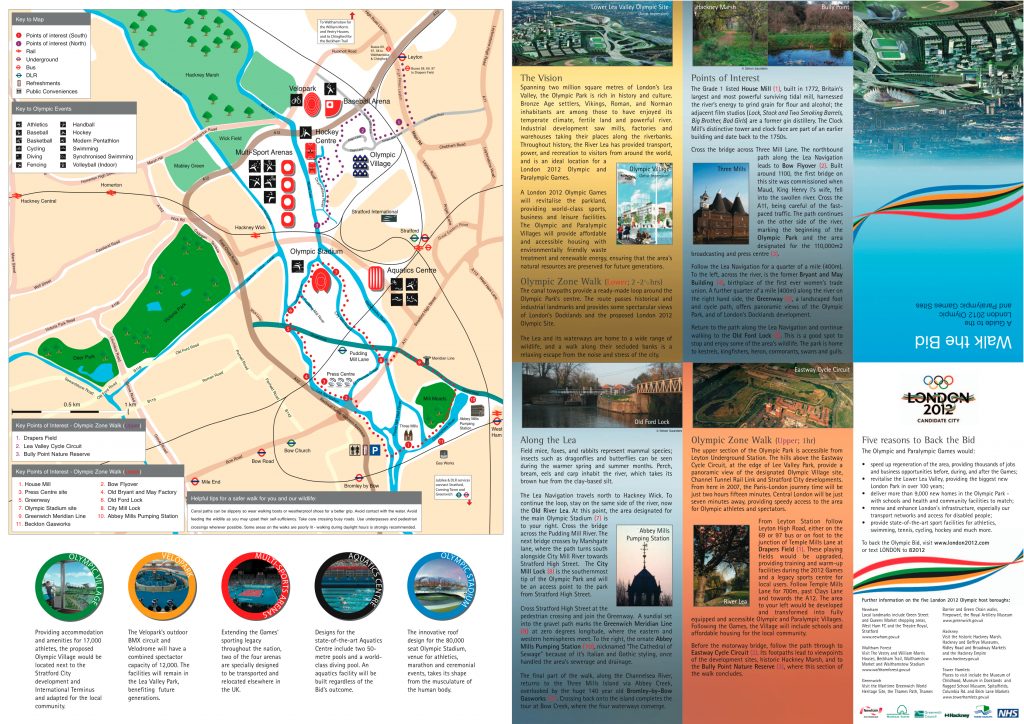

THE PARK

The International Olympic Committee specifies the need for an integrated park. The IOC also demands that athletes should be accommodated in a village and not be required to walk for more than twenty minutes. The Olympic Park has been presented as ‘1500 landscaped acres’ representing ‘one of the biggest new city centre parks in Europe for 200 years.’ This ignores the fact that much of the Lower Lea Valley, where the park will be built, is an extensive network of waterways with important wildlife habitats on a key migratory route.

For centuries ‘Parkification’ has been the instrument of choice for colonising the urban periphery, hinterlands and backwaters, socially cleansing those edgy zones of social marginalism and transgression, displacing the grey economies and polluting industries, taming the wild.

Although it has no formal position on the Olympics, the River Leas Trust, an environmental charity that works to preserve this wild environment, have told the London Olympic bid committee that ‘landscaping’ the area is inappropriate, particularly in the way represented in the ‘artists impression’ that the bid supporters are so proud of.

Hackney Marshes, once ancient common lands called Lammas Lands, were bequeathed in the 1890s by the Settlement of St. Mary Eton to the people of Hackney in perpetuity for recreational use as open space. Since that time Hackney Marshes has been home to amateur league football. Most London footballers have played there. Hackney Marshes holds the world record for the highest number (88) of full-sized football pitches in one place. On a typical Sunday, over 100 matches are played by amateur teams competing in several local leagues.

Johnny Walker, Chairman of Hackney and Leyton Sunday Football League, talks about the substructure under Hackney Marshes created by WWII, and the effects of changes due to the London Olympics 2012

At a meeting set up by the Hackney Environment Forum on 24 July 2003, Neale Coleman, the London mayor’s advisor on the Olympic bid, countered fears that Hackney would lose its open space to stadium and temporary facilities, reassuring the meeting that there was ‘no question of permanent or temporary facilities on any part of Hackney Marshes’. Attached to the planning applications is a condition stating that the developing agency must provide exchange land for Common Land and open space taken up by the Olympic developments, a procedure required under the 1981 Acquisition of Land Act.

However, at the end of 2005, the New Lammas Lands Defence Committee were told by Hackney Council Cabinet Member for Regeneration, Guy Nicholson, that planners were defaulting on this obligation. Since then, a clause has been inserted in the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Bill to remove this imperative. Anne Woollett, Chair of the Hackney Marsh User Group, states:

The Games cannot make any claims to being ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ while they steal Common Land, public open space and sports pitches for an Olympic car park. The London Development Agency (LDA) have now declared […] that they are not going to provide exchange land for East Marsh. It appears that the LDA have simply lobbied to legislate away their own statutory obligations.

Many are suspicious that when the car park is no longer needed it will be built on.

Hidden away on the Olympic site is Manor Gardens Allotments. Founded by philanthropic aristocrat Major Arthur Villiers before WW1, the allotments have been feeding over 150 local East End families ever since. The LDA wants the site levelled and transformed into the central concrete walkway down the spine of the Olympic Park. Apparently, saving this unique and rare place by going around or over the allotments for a few weeks was not an option for security reasons.

After almost two years of meetings with the LDA, the Manor Gardening Society have had enough of broken promises and delays and on 27 April 2007 they issued Judicial Review proceedings against them. Phil Michaels, head of legal at Friends of the Earth’s Rights and Justice Centre, who represent the allotment holders said:

This is an important case about broken promises and local communities. The LDA made clear and consistent promises to the community that their allotments would be relocated so that they could stay together. They have now decided to break that promise. If the authorities are not willing to honour their promises then the Court has to step in.[9]

The IOC refers to respect for the environment as the ‘third pillar of Olympianism’. The Sydney Bid Committee failed to note that Homebush Bay, the Olympic site, was heavily contaminated with dangerously high levels of dioxin, asbestos, heavy metals, and phthalates. The New South Wales government commissioned four scientific analyses and remediation plans for the site between 1990 and 1992 but took no action to avoid jeopardising the bid. When exposed, Olympic organisers accused environmentalists of being ‘unpatriotic and ‘un-Australian’.[10]

REGENERATION: THE REALITIES

David Higgins, Chief Executive of the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), states:

Our challenge is to successfully manage both the requirements of the Games and the long term regeneration of East London. Achieving both of these will bring fantastic opportunities for the whole of the UK.

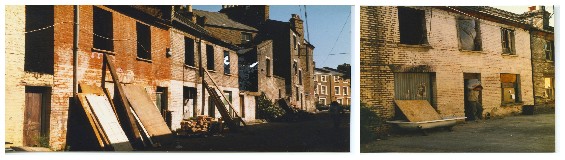

In the past 20 years, there has been wave after wave of ‘regeneration’ in East London, each scheme spending huge amounts of public money. While claiming to be solving the same basic problems associated with poverty and ‘social exclusion’, the schemes seem never to have achieved their stated aims. Primarily, because their real aim has been to promote gentrification. During the Thatcher era, it was to be via the ‘trickle down effect’; now, gentrification is justified as being about ‘mixed-tenure’ and ‘social diversity’. But whichever prism you chose to view it through, the fact is that regeneration is simply the process of privatisation of housing and public space.

Lord Coe has explicitly stated his aim to ‘put London in the same bracket as the Barcelona games’. An ominous comparison. David Mackay, one of the leading architects of the Barcelona Olympics, whose firm MBM Arquitectes built the beach and the Olympic village, has said:

For Barcelona, [the Olympics] were a pretext, an excuse to improve the city.

Mackay calls the London Olympic plan a ‘missed opportunity’, a ‘thing that has arrived from out of this world and been plonked down in the Lea Valley’, anarchitectural theme city […] concentrated on iconic buildings rather than the recovery of the Valley.

London will build a new Olympic stadium, a velopark – a set of cycling arenas (in fact London mayor Ken Livingstone confirmed in February 2005 that the proposed £22 million velodrome and velo-park would be built with or without a successful Olympic bid) – and new athletics, aquatics and hockey centres. Mackay is critical of all these. The master plan, he told the Evening Standard, shows;over-construction. … It’s all concentrated according to the best desires of the International Olympic Committee, who want everything for their three week pageant. They’ve gone too far. It’s not for Londoners.

Genuine regeneration benefits local residents; when ‘regeneration’ means displacement it is little more than a land grab. In Barcelona, the construction of the Poblenou Olympic Village displaced a working class neighbourhood. In Atlanta, the Olympics provided the opportunity to convert Techwood/Clark Howell public housing, the oldest in the US, into mixed use development and to displace low-income residents (mainly African American) from the downtown area. In total, about 450 public housing units were lost. The estates were situated on prime real estate, near the Georgia Institute of Technology and opposite the corporate HQ of Coca-Cola.[11]

In Beijing, it is thought that around 1.4 million people have been forcibly moved, some illegally. The number of traditional hutong neighbourhoods, made up of courtyard houses, has been reduced from 6.5 thousand to 500 as a result of clearances for the 2008 games.

LEGACY

Evidence suggests that new sports facilities have an extremely small (and perhaps even negative) effect on overall economic activity and employment in a given area.[12] Stadia rarely earn anything approaching a reasonable return on investment and sports facilities attract neither tourists nor new industry. One legacy of the London Olympics might be high maintenance facilities and a huge debt. After all, Montreal took 30 years to pay off the debt it incurred building their Olympic site.

According to the British Olympic Association, the London Games ‘will drive many of our youngsters to take part in sport and pursue dreams of becoming an Olympian.’ Jacques Rogge, president of the IOC, is planning a Youth Olympics for 14-18 year olds in 2010.

But behind Rogge’s dream is another myth-busting admission: the Olympics is not about sport but about watching television. Since the average age of the television audience for the track and field events is over 40, it is difficult not to see the Youth Olympics primarily as an attempt to attract a more youthful sector. For all but the relatively miniscule number of people in the stadium, the Olympics is a televised event. In Australia, a very outdoor society, it was television viewing figures rather than sports activities that increased after the Sydney Olympics.

OLYMPIC IDEALS AND URBAN PLANNING

The planning applications for the Olympic Park were submitted by the ODA to the ODA Planning Decisions Team (PDT) on 5 February 2007. The 15-volume, 10,000 page document included plans for 2.5 km2 of new sporting venues, highways, bridges, river works, utilities, parks, and open spaces. Plans for the park show it will be very densely built.

The application was subject to a statutory 28 days consultation period, later extended to six weeks, to allow members of the public to give their comments. There were many objections lodged, a major one being about the inadequate time for public consultation and woeful access to the application documents. The time period given to digest, consider, and prepare responses to one of Europe’s biggest ever planning applications was completely unrealistic, and further exasperated by the lack of access to documents, either online, in public libraries, or even at the ODA offices themselves. The complete set of planning documents available from the ODA in hard copy costs £500. DVDs were provided free-of-charge to representatives and those in the ODA/LDA, but were not available to local community groups.

It is difficult to see how the ODA has complied with The European Environmental Impact Assessment Directive which applies to these applications.[13] The directive provides that, the public concerned shall be given early and effective opportunities to participate in the environmental decision-making procedures referred to;[14] and that, reasonable time-frames for the different phases shall be provided, allowing sufficient time for informing the public and for the public concerned to prepare and participate effectively in environmental decision-making subject to this article.’[15]

Complaints about the absence of meaningful consultation, a lack or withholding of information, and manipulation of facts, are commonly directed at regeneration projects. As one resident says:

I was looking at an exhibition about the Olympic site and thought… Hang on! That’s where I live!

THE WINNERS

Laing O’Rourke, in partnership with Mace Ltd. (project management) and environmental evaluation company CH2M Hill (together called the CLM consortium), won the contract to manage construction of the 80,000-seat Olympic Stadium and the Athletes’ Village. Happily, the CLM consortium has worked on five previous Olympic Games: Torino 2006, Athens 2004, Salt Lake City 2002, Sydney 2000, and Atlanta 1996.[16] The awarding of the management contract to CLM caused some controversy within both the industry and Parliament on the grounds that construction tycoon Ray O’Rourke had given a substantial donation to ‘Tony Blair’s 2012 bid team’ and substantial help in kind.[17]

The real winners are the IOC themselves, however. In the Athens games, they made a billion dollars in TV rights alone. The IOC enjoys tax-free status despite not being a charity, a religion, or a non-profit organisation. And to be on the safe side, its members enjoy diplomatic immunity.

THE LOSERS

The losers are often the most vulnerable members of society. In Atlanta, the Metro Atlanta Task Force for the Homeless documented the arrest of 9,000 homeless people in a policy of ‘arrests and relocation’ during the year before the Olympics. In Athens, 140 Roma from the Marousi community were forcibly evicted. The Clays Lane estate in East London, Europe’s second largest purpose built housing cooperative, was set up in the early 1980s to address the lack of housing for young single people in the area. It was initially funded by organisations including Newham Council and the University of East London. The site is large enough to house approximately 450 people. Now, the residents have been displaced under a Compulsory Purchase Order (CPO) issued by the London Development Agency (LDA) to make way for the development of the Olympic Village.

Also among the losers will be those deprived of funding by the Olympic budget. The Lottery (which, given the miniscule chance of winning, is basically a tax on the daft) will lose £112.5 million to help pay for the Olympics. This amount would otherwise have gone to ‘good causes’. The Arts Council of Great Britain recently slashed the ‘Grants for the Arts’ scheme funding by a third, from £83 million to £54 million, the first Olympic raid on the Arts Lottery fund. This money would have gone to around 5,000 arts projects.

In March 2004, a cross-party committee of MP’s called the earmarking of money for the Olympics ‘a straightforward raid’ on Lottery funds for projects outside of London. The committee argued that the redirection of funds breached the government’s promise not to use Lottery cash to support schemes that should be funded through general taxation. It will be communities in East London and other deprived areas of the country who will suddenly find it harder to secure funding.

Protesters tour Olympic construction sight on canal boats in East London, Olympics 2012

NATIONAL MEGA PROJECTS

The postwar Olympic games are less sporting events than mega development projects. For every host city, the Olympics is an instrument for major urban restructuring on a scale that would otherwise be beyond the planners’ wildest hopes and dreams. The glow from the Olympic torch shines so bright it bleaches out the flickering flames of protest.

The governments of all host nations exploit the Games for self-aggrandisement. From Berlin 1936 to Beijing 2008, regimes have used the opening ceremonies to parade the Games as the fruit and embodiment of their ideology. The 1973 games in Munich, for example, saw politics return to German sport as Cold War tensions came to a head.[18] The American-led boycott of Moscow 1980 was another recognition of the ideological instrumentalisation of the Games, as was the retaliatory boycott of Los Angeles 1984 by the Soviet Union and 13 Communist allies. In the run up to the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, China wants to take the Olympic Torch through Taiwan and Tibet.

One can only fantasise about the cultural kitschifaction that will feature in the London opening ceremony. In the Expo 2000 UK pavilion, Battersea Power Station, an icon for degeneration, was featured heavily – so don’t expect irony.

Of course, Britain’s major cultural legacy is its colonial past, currently unravelling most visibly in Iraq. Colonialism and regeneration have much in common. After all, one of the classic tricks of British colonialism was to present the land being taken over as ‘empty’. Colonialism also likes to rename. Or, as it is called today, ‘re-brand’. The idea is to re-appropriate culturally what has been taken physically. The branders can either sweep away all that existed before by calling it ‘My-Land’. Or enlist the past, one as distant, romantic, and mythical as possible, to present as natural what in fact is an irreversible lurch in the opposite direction. To cite the deputy Chairman of the Interbrand Group, Tom Blackett:

The development that will take place in preparation for the 2012 Olympics will change profoundly the character of the old East End; much of the squalor and dereliction will be swept away, and even areas developed by the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority will be transformed. […] The vast site [ …] will acquire an entirely new image, and with that it needs a new name. But it has to be a name that will last, a name that will capture the glory of the 2012 Olympics and help signify the rebirth of the area. ‘Lammas Lands’ would honour the spirit of the past; it is a name that is synonymous with recreation and the public good, and carries with it a long tradition of sport in East London.

Why not call it the ‘East End of History’?

THE FUTURE

As people who deliberately kick the hornets’ nest over love to say: ‘We are where we are.’ Sure, the London Olympics will go ahead, maybe not on time or on budget, but they will at least manage to destroy all that is currently there by turning it into Europe’s biggest building site. But the Olympic circus must stop. London must be the last nomadic Olympics. After 2012, the Games should stay in one place: perhaps Athens, Los Angeles or Atlanta (who cares?). The complex, not the IOC, should have ambassadorial status and be insulated from the host country. The athletes should represent themselves, not a country. We should see the world’s diversity through faces, not flags.

Competitive sport at this level is too specialist for it to be participatory for a wider public and it is a myth that the centralisation of specialist facilities does anything to help wider participation in sport. It would be better for the athletes if good, fixed facilities were established instead of the wasteful and destructive cycle of makeshift and make do. The money saved could be better invested in spreading around the world accessible local sporting facilities at a community level. That would be a true Olympic legacy.

But more importantly, it is clearly unacceptable for a self-elected, unaccountable body like the International Olympics Committee to decide the fate of our cities. It is not about sport but a process whereby business interests lobby and encourage democratically elected local governments to commit limitless public money and dedicate urban priorities to hosting the Games. The IOC, through the issuing of exclusive rights and franchises, and by ruthless brand protection, in turn invigorates and gives free reign to those business interests. The momentum created by the need to ‘put on a good show’ irrevocably distorts and rearranges our cities according to private concerns. In the national interest, extraordinary powers are exercised to overcome democratic structures, opposition, and planning constraints. For the East End, it is not looking good. The area will slowly get turned into a matrix of gated housing and shopping complexes, clustered in a tamed, risk-averse landscaping linked by high security jogging friendly ‘green’ pathways.

As they say in Cockney rhyming slang: then we’re ‘McDonald Ducked’.

Further Information

The best source of info and updates on the London Olympics is Games Monitor, http://gamesmonitor.org.uk

Footnotes

[1] Guardian Unlimited, 8 March 2007.

[2] The Guardian, 8 March 2007.

[3]The Independent, 08 March 2007.

[4] Sarah Glynn, ‘Playing the ethnic card – politics and ghettoisation in London’s East End’, online papers archived by the Institute of Geography, School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, 2006, http://linkme2.net/ce

[5] East End Life, 15-21 November 2004.

[6] ’2006 Multi-Storey Housing’, in: Review of Architecture, vol. 3, 2006, p. 302.

[7] A. Fraser, BBC Sport, 16 August, 2005.

[8] BBC Sport, 16 August, 2005.

[9] Manor Gardens Press Release, 28 April 2007.

[10] Helen Jefferson Lenskyj, Progressive Planning Magazine, Fall 2004.

[11] Peter Phibbs, Progressive Planning Magazine, Fall 2004.

[12] See: Roger G. Noll and Andrew Zimbalist, Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, Brookings Institution Press, 1997.

[13] Directive 85/337/EEC as amended.

[14] Ibid, 6(4).

[15] Ibid, 6(6).

[16] Contract Journal, 30 August, 2006

[17] Evening Standard, 3 September 2006, in the run up to the IOC’s decision.

[18] On the ideological mise en scène of the Munich Games in 1973, see: Uta Andrea Balbier, ‘Zu Gast bei Freunden. How the Federal Republic of Germany Learned to Take Sport Seriously’, in: Mittelweg 36, 2, 2006. English translation published by Eurozine : http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2006-06-09-balbie…

This is an edited version of an article that appeared first on the Eurozine website entitled ‘Fish ‘n’ Freedom Fries’ : http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2007-05-25-saunde…

Mark Saunders is a documentary film maker living in London. His films and photography are available at http://www.spectacle.co.uk

Sign up to our Newsletter for more information about our ongoing projects.

Spectacle Homepage

Like Spectacle Documentaries on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram, Vimeo, Youtube and Linkedin