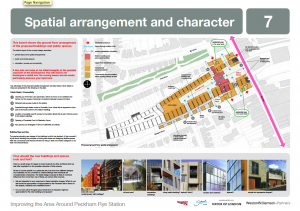

The area surrounding Peckham Rye Station, set for redevelopment by Network Rail and Southwark Council, has been dubbed the ‘Gateway‘. Their intention to cash in on Peckham’s recent prosperities endangers the independent, artisan businesses within the arches and the 1930’s building surrounding the station. In January, the plans were revealed detailing commercial and retail units, and seven-story’s worth of luxury accommodation. While community efforts to halt the construction are bubbling, with council meetings being called and the local distribution of flyers, it is still important to note the strategic use of limiting language by various bodies of power and not to adopt such terms ourselves, or face being pigeonholed.

The area surrounding Peckham Rye Station, set for redevelopment by Network Rail and Southwark Council, has been dubbed the ‘Gateway‘. Their intention to cash in on Peckham’s recent prosperities endangers the independent, artisan businesses within the arches and the 1930’s building surrounding the station. In January, the plans were revealed detailing commercial and retail units, and seven-story’s worth of luxury accommodation. While community efforts to halt the construction are bubbling, with council meetings being called and the local distribution of flyers, it is still important to note the strategic use of limiting language by various bodies of power and not to adopt such terms ourselves, or face being pigeonholed.

A simple Google search produces interesting definitions for the term ‘Gateway’ – “a place regarded as giving access to another place” and “a device used to connect two different networks”. In the context of the station, the overground links and rail services certainly do give immediate access to central Peckham and all of the available industries around Rye Lane. However, by defining the area as such, limits it to being perceived only as a port of access and undermines it as an attraction in itself.

A simple Google search produces interesting definitions for the term ‘Gateway’ – “a place regarded as giving access to another place” and “a device used to connect two different networks”. In the context of the station, the overground links and rail services certainly do give immediate access to central Peckham and all of the available industries around Rye Lane. However, by defining the area as such, limits it to being perceived only as a port of access and undermines it as an attraction in itself.

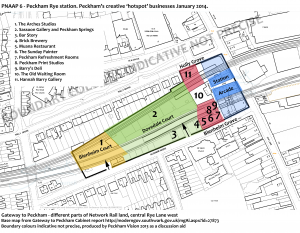

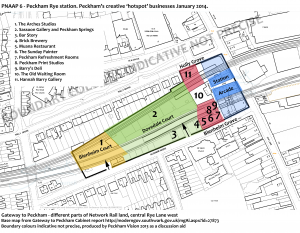

Peckham Vision illustrates (above) the locations of various creative and cultural businesses on the station redevelopment plan. Similarly, our previous blogs have tried to highlight how the Peckham ‘Gateway Area’ is in fact a place full of creative enterprises, long-standing businesses and new, independent initiatives such as bars and breweries, galleries and studios. All of which are contributing to a gradual increase in footfall and popularity of Peckham, which is attracting people from all over town. Yet the plans have chosen to ignore Blenheim Court, Blenheim Road, Dovedale Court, Holly Grove and the Station Arcade as an area of increasing enterprise and local economic advantage. Instead, the whole area has been reduced to an entry and exit point for central London commuters who will take up the unaffordable housing, and the gentrified twenty-somethings flocking to Frank’s of a summer’s eve. All of the connotations point away from existing residents, business owners and the local community who actually use, live and breathe the space every day.

Peckham Vision illustrates (above) the locations of various creative and cultural businesses on the station redevelopment plan. Similarly, our previous blogs have tried to highlight how the Peckham ‘Gateway Area’ is in fact a place full of creative enterprises, long-standing businesses and new, independent initiatives such as bars and breweries, galleries and studios. All of which are contributing to a gradual increase in footfall and popularity of Peckham, which is attracting people from all over town. Yet the plans have chosen to ignore Blenheim Court, Blenheim Road, Dovedale Court, Holly Grove and the Station Arcade as an area of increasing enterprise and local economic advantage. Instead, the whole area has been reduced to an entry and exit point for central London commuters who will take up the unaffordable housing, and the gentrified twenty-somethings flocking to Frank’s of a summer’s eve. All of the connotations point away from existing residents, business owners and the local community who actually use, live and breathe the space every day.

The use of the term, as can be seen in the statistics above, began to peak around the 1980’s – a stark correlation with the Thatcher era and large-scale, government-funded programmes for urban redevelopment. The Thames Gateway project, of the same name, is a perfect example.

This was a Thatcher regeneration investment to turn brownfield land into 160,000 new homes, rejuvenate towns and create 180,000 new jobs along the Thames estuary, from east London, through Kent and as far as Southend-on-Sea and the Isle of Sheppey in Essex. The sheer size of the development meant that the entire region was looked upon not as individual, bottom-up improvements spanning three counties and 16 local government districts, but as a singular overhaul of general degradation. It was former conservative deputy Prime Minister, Michael Heseltine who defined the area as a ‘Gateway’ during a helicopter tour of east London in 1979, and in doing so reduced the home of over 3 million people to “a place regarded as giving access to another place“.

This was a Thatcher regeneration investment to turn brownfield land into 160,000 new homes, rejuvenate towns and create 180,000 new jobs along the Thames estuary, from east London, through Kent and as far as Southend-on-Sea and the Isle of Sheppey in Essex. The sheer size of the development meant that the entire region was looked upon not as individual, bottom-up improvements spanning three counties and 16 local government districts, but as a singular overhaul of general degradation. It was former conservative deputy Prime Minister, Michael Heseltine who defined the area as a ‘Gateway’ during a helicopter tour of east London in 1979, and in doing so reduced the home of over 3 million people to “a place regarded as giving access to another place“.

Similarly, last year’s Tower Hamlets Whitechapel Vision Masterplan aimed at the regeneration of the area to transform it “into a key destination for London“, uses the the word again. From page 8 of the ‘vision’:

The creation of “entrance gateways” will help to improve first impressions, create a sense of arrival and define Whitechapel as a place and destination in its own right. This can be achieved through high quality buildings and public realm improvements at these gateway junctions.

Despite the complete disregard that Whitechapel is a already a place of interest for many Londoners, the onus on developing the area alongside new Crossrail networks for the enjoyment of newcomer’s “first impressions”, without recognition for the people that already live and work there, just stands to show where the loyalties of our councils lie. The grandiose over-expenditure on the part of Network Rail for amenities already available in Peckham, such as bars, galleries and artisan studios, reeks of this outmoded, 80’s planning.

The same generalisations can be said for things like the Gateway Drug Theory, which suggests that drugs such as alcohol and cannabis create a pathway into harder drugs, addiction and crime. Various sporadic experiments have supported and refuted the hypothesis, but all-in-all, the term used is limiting and sees populations as a generalised whole, detracting credit from the rational, decision-making individual.

Organisation, This Is Not A Gateway, was formed to create a platform for people who care about the future of our streets to discuss, debate and critique the ever-changing urban policy of cities and towns. They argue that all too often, decisions regarding vast redevelopment of urban areas are isolated to a small population of upper-middle class, white men that will likely never step foot on the soil they homogenise. In describing the choice of name for the organisation, they put it perfectly:

There is no beginning or end of a city, there is no place of entry and exit, there is no entrance that can be opened, there are no gateway texts, no gateway knowledges. In choosing to recognise ‘gateways’ we give others the ability to create boundaries, borders and limitations to our lives.

The historical use of ‘Gateway’ has always been about management. It reduces and simplifies places and people so that they can be effectively herded and categorised, which establishes control.

Eileen Claridge, the sarcastic Network Rail representative instructed to attend the January 18th ‘public consultation’ meeting, who kindly stated that corporation was “not a charity”, is the terrifying example of this control tactic. In Network Rail’s 2012 winter newsletter, Eileen was interviewed about her new position as one of eight “asset development surveyors who look after enhancement projects for Network Rail Commercial Estate”:

Eileen Claridge, the sarcastic Network Rail representative instructed to attend the January 18th ‘public consultation’ meeting, who kindly stated that corporation was “not a charity”, is the terrifying example of this control tactic. In Network Rail’s 2012 winter newsletter, Eileen was interviewed about her new position as one of eight “asset development surveyors who look after enhancement projects for Network Rail Commercial Estate”:

What does your job entail?

We identify and develop potential new income for commercial estates.

What are the challenges?

We’re tasked with raising the company’s income

by finding brand new opportunities.

What would you be doing if it weren’t this job?

I’d quite like to be a mounted policeman!

I can only draw comparisons to the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 at Eileen’s closing statement.

Please feel free to leave your comments below.

Get in touch if you would like to contribute to our film about the Peckham Rye Station and Gateway Area Redevelopment Project. Just email: production@spectacle.co.uk

See Peckham for more blogs and information.

Or visit PlanA, our general blog on urbanism, planning and architecture.

Spectacle homepage

Like Spectacle Documentaries on Facebook

Follow SpectacleMedia on Twitter

Network Rail Winter Newsletter 2012

Network Rail Winter Newsletter 2012

Peckham Peculiar

Peckham Peculiar